Is a Schedule K-1 By Itself Enough to Prove LLC Membership?

November 19, 2018

Let me say up front, I don’t claim to know the answer to the question posed in this post’s title, or pretend there’s a simple yes-or-no answer. It very well may be that the answer depends on the unique facts and circumstances in any given case, including the one discussed below.

Let me say up front, I don’t claim to know the answer to the question posed in this post’s title, or pretend there’s a simple yes-or-no answer. It very well may be that the answer depends on the unique facts and circumstances in any given case, including the one discussed below.

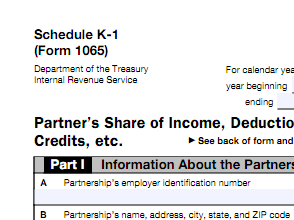

Having said that, take a look at a Schedule K-1 in the tax return of a limited liability company. I’ll make it easy; click here for the 2017 K-1 form available on the IRS’s website. Now tell me, in the Part II “Information About the Partner” section of the form, do you see a check box for a taxpayer who is a non-member/assignee/holder of an economic interest in an LLC?

That’s right, you don’t. As pertains to LLCs, the only choices are “LLC member-manager” or “other LLC member.”

I’m not a tax expert, but I’m fairly confident it makes no difference whether one or the other of those boxes is checked for a non-member assignee of an LLC interest, at least for tax purposes. But it can make a night-and-day difference for state law purposes to a litigant seeking to enforce rights as the assignee of a membership interest — be it to secure judicial dissolution, to enforce management, voting or inspection rights, or to prosecute derivative claims — and who relies solely on a K-1 as proof of his, her, or its member status.

It makes a difference because, under New York statutory and case law, absent provision in an operating agreement to the contrary, an assignee, non-member holder of an economic interest in an LLC has no standing to assert any of those rights or to obtain any of those remedies.

I’ve encountered the issue a number of times in my business divorce travels, almost always involving LLCs with no written operating agreement and that don’t observe governance formalities. It’s also an issue that surfaced in a recent decision in which the court held that the plaintiff, whose complaint asserts both direct and derivative claims for breach of fiduciary duty, and who was not an original member of the subject LLC and acquired his interest by undocumented assignment, established his member status based on his K-1, apparently in the absence of any written agreement with the other members or other evidence of any formal consent to his admission as a member. Rosin v Schnitzler, 2018 NY Slip Op 32320(U) [Sup Ct Kings County Sept. 4, 2018].

Judging by the over 20 motions and 366 docket entries to date in this three-year old case, Rosin looks like a very messy, very convoluted dispute over the plaintiff’s alleged ownership and management rights in a pair of companies in the snack food business, one an LLC and the other a corporation. I’m only going to focus on the LLC, and only to the extent of the court’s recent disposition of the plaintiff’s summary judgment motion in which it found, based solely on the K-1, that the plaintiff established his one-third ownership as a member of the LLC and can proceed to trial on his claims.

The Plaintiff’s Motion to Establish His Membership Interest

I haven’t taken a deep dive into the parties’ voluminous supporting and opposing affidavits and exhibits, so I won’t pretend familiarity with the factual minutiae of the contentious history of the parties’ interactions that, according to the plaintiff, resulted in the conveyance to him of an interest in the LLC in exchange for the substantial sums he invested. What does seem clear is that the plaintiff was not an original member of the LLC when it was formed in 2012 and that, whatever interest he later acquired, it came via an undocumented assignment from another member or members.

In broad strokes, the plaintiff’s position relied on disputed oral agreements with the two defendants, monies he paid into the LLC, and its 2014 tax filings including K-1s issued to the three litigants. The check box in Part II of the K-1s issued to the plaintiff and one defendant identify each as “General partner or LLC member-manager” and the other defendant as “Limited partner or other LLC member.” The K-1s issued to the former pair show each as having a one-third profit interest and 50% loss and capital interests, and the latter as having a one-third profit interest and 0% loss and capital interests.

In their opposition to plaintiff’s motion, the defendants relied on section 603 and section 604 of the LLC Law, the former providing that the “only effect of an assignment of a membership interest is to entitle the assignee to receive, to the extent assigned, the distributions and allocations of profits and losses to which the assignor would be entitled,” and the latter providing that, except as otherwise provided in the operating agreement, “an assignee of a membership interest may not become a member without the vote or written consent of at least a majority in interest of the members, other than the member who assigned or proposes to assign such membership interest.”

In other words, the defendants argued, even assuming plaintiff can show that some interest in the LLC was assigned to him, nonetheless he lacked standing to assert claims to enforce management rights because there exists no evidence of a vote or written consent by the other members to his admission as a member, as required by LLCL § 604. Tellingly or not, in their memorandum of law the defendants did not comment on the K-1 issued to the plaintiff. One of the two defendants submitted an affidavit merely stating that he had nothing to do with the K-1’s preparation and never received a copy of it.

In his reply, the plaintiff cited the decision in BMM Four, LLC v BMM Two, LLC for the proposition that the filing of tax returns identifying LLC members can serve as a writing evidencing a transfer of membership. In that case, the court upheld the validity of the transfer of a 100% LLC membership interest from one spouse to another — the litigation was not between the spouses, but between the LLC and co-tenants in common in a real property — as evidenced by a tax return, citing a provision in the LLC’s operating agreement authorizing it to “keep books and records either in written form or in other than written form.”

The Court’s Decision

In his decision in Rosin, Brooklyn Commercial Division Justice Lawrence S. Knipel began his analysis by noting that “[w]here, as here, there is no valid operating agreement, the statutory default provisions set forth in the [LLC] Law apply,” followed by quotations from the relevant provisions in LLC Law §§ 603 and 604 cited by the defendants.

But that’s as far as the defendants’ argument got. Justice Knipel next agreed with the plaintiff that “[a] tax return can constitute evidence of a written assignment,” citing not only the BMM Four case but also quoting from the Court of Appeals’ oft-cited opinion in Mahoney-Buntzman applying quasi-estoppel doctrine to hold that a party to litigation may not take a position “contrary to declarations made under penalty of perjury on income tax returns.” Justice Knipel concluded:

The plaintiff has established, by way of [the LLC’s] federal and state tax returns, that he was a one-third owner of all the membership interests in [the LLC]. In opposition, [defendant] has failed to raise a triable issue of fact, as he has not challenged the accuracy of [the LLC’s] federal and state tax returns which listed the plaintiff as a one-third owner of all the membership interests in [the LLC].

Except by implication, the court’s decision did not directly address whether the plaintiff’s acquisition by assignment of his interest in the LLC, as evidenced by the tax filings, conveyed an economic interest in the LLC only, or effectuated his admission to the LLC as a member with management and voting rights, and standing to assert claims based on those rights including the right to assert derivative claims.

The Defendants’ Motion for Clarification

The defendants subsequently filed a motion for clarification of the court’s decision in which they asked the court to specify that, under LLC Law § 604, its finding of a valid assignment to the plaintiff did not give him voting or management rights as a member. (The motion did not raise, however, the issue of plaintiff’s standing as an assignee to pursue derivative claims.)

In opposing the motion, the plaintiff pointed — you guessed it — to the check box on his K-1 identifying him as “General partner or LLC member-manager.”

In a handwritten order dated October 10, 2018, Justice Knipel granted the motion to the extent of declaring that the court’s prior finding that plaintiff “was a one third owner of all membership interests” in the LLC “[b]y its terms . . . was not in any way limited and this court declines to limit said interest.”

The case currently is scheduled for non-jury trial later this month.

As noted at the top of this post, I’m in no position to suggest that the outcome in Rosin was right or wrong. I’m merely sounding an admittedly wonkish and wistful note that the parties (and therefore the court) did not more robustly address the issue of the plaintiff’s standing to sue as assignee and, more specifically, whether the K-1 by itself sufficed to satisfy LLC Law § 604’s requirement for admission to membership.

But I won’t despair. It’s a recurring fact pattern, bound to make an appearance in another case in which, hopefully, the issue will garner more intense scrutiny.